Langhorne Speedway

By Kyle Ealy

Langhorne, Penn. – A.J. Foyt once said about Langhorne Speedway, “That was a track that separated the men from the boys. On the list of toughest tracks to run, you'd have to put it at #1.”

Built in 1926, all other racing courses up to that time were fairground horse tracks, but Langhorne was the first one-mile dirt track built specifically for cars. The “Horne” was shaped like a perfect circle. Known as "The Big Left Turn," Langhorne was for many years the world's fastest track of its size, despite being unpaved. The unique layout meant that drivers drifted around virtually the entire circuit, usually with the throttle wide open.

Turn two was affectionately known as “Puke Hollow”, a name coined in in the track’s first year of existence. During a race in the worst of Pennsylvania's summer heat, a driver was overcome by the combination of humidity, dust, bumps, and fumes and after exiting his car, he proceeded to lose his lunch right there. "One of the spectators yelled, 'He's throwing up there in Puke Hollow,”’ and the name stuck.

Langhorne held every race imaginable including jalopies, modifieds, stock cars and even motorcycles, but the Indy-style cars would be one of the more popular events of the season.

Starting in 1940 and continuing until 1970, the Indy-style championship cars would converge on Langhorne Speedway each June and run a 100-mile event.

Under American Auto Association (AAA) sanctioning, Duke Nalon would win the first two 100-milers, on June 16, 1940, and June 22, 1941. In 1942, however, the United States government banned all forms of auto racing due to America's involvement in World War II. As a result, Langhorne sat idle and did not host a race of any kind until 1946.

With the war over, racing was back stronger than ever and on June 30, 1946, over 50,000 spectators watched Rex Mays of Los Angeles, Calif., flash across the finish line ahead of Indianapolis 500 winner George Robson to win the 100-miler in 1 hour, 10 minutes and 28 seconds. May’s winning share of the $14,000 purse was $3,600.

A record 52,000 would see “Wild” Bill Holland of Bridgeport, Conn., win the 100-miler on June 22, 1947. Holland gunned his Offenhauser around the one-mile oval on 1 hour, 8 minutes and 23 seconds, to finish over two laps ahead of Emil Andres of Chicago.

Walt Brown of Massapequa, N.Y., would win the 100-miler on June 20, 1948. The race was appropriately named the “National Convention Sweepstakes” in honor of both the Democratic and Republican Conventions being held in nearby Philadelphia that July. Brown, who won the race in 1 hour, six minutes and 55 seconds, roared to the front after favorite Ted Horn dropped out with engine trouble after 66 laps.

The 1949 100-miler would be moved to October for one reason or another. Instead of suffering through the June heat, officials decided that race fans should freeze instead and only 10,000 showed up on October 16 to see Johnnie Parsons of Van Nuys, Calif., win the race in 1 hour, 4 minutes and 56 seconds, securing his fifth national championship.

The race would be moved back to its June slot in 1950 and on June 25, Jack McGrath of South Pasadena, Calif., won before 18,000 onlookers. McGrath gunned his racer into the lead when race leader Duke Nalon ran out of gas with only 5 miles to go. McGrath’s winning time was 1 hour, 7 minutes and 47 seconds and the up-and-coming driver earned himself $7,500.

On June 25, 1951, Tony Bettenhausen of Tinley Park, Ill., drove the Belanger Special to victory in the 100-miler before almost 24,000 fans. Bettenhausen won in the time of 1 hour, 4 minutes and 57 seconds, beating the one-legged Bill Schindler of Freeport, N.Y., by half a mile.

There would be no Indy cars or 100-milers in 1952 nor in 1953. This writer could find no reason for its absence those two years.

But they would return on June 20, 1954, and before 22,000 fans hungry for fast action, Jimmy Bryan would give it to them, shattering the track record in winning the 100-miler in 1 hour, 1 minute and 30 seconds. The 26-year-old Phoenix, Ariz., speed demon, who had badly burned his foot a month earlier at Indianapolis, mashed on the gas pedal and smashed the 13-year-old record previously held by Duke Nalon.

The 1955 race was split in halves; with the race originally taking the green on June 19 but after 44 laps, called because of rain. The race would pick up the following Sunday, June 26, and once again Jimmy Bryan would be the class of the field. Covering the event in 1 hour, 2 minutes and 40 seconds, Bryan finished 10 seconds ahead of Indy 500 winner Bob Sweikert.

Citing safety concerns, the American Auto Association would withdraw from auto racing at the end of 1955 and the United States Auto Club would start sanctioning events beginning with the 1956 season.

The 1956 race would see a major upset as George Amick of Los Angeles, Calif., fought a host of favorites and the usual sultry Pennsylvania humidity to win the 100-miler on June 24. Amick, who started sixth, pulled into the lead on lap 70 when accidents and pit stops started plaguing the leaders. Defending winner Jimmy Bryan, pole-sitter Bill Garrett, Bob Veith and Pat Flaherty would all fall victim to Langhorne and Amick would cop his first major Indy-car victory.

One hundred miles in less than an hour seemed almost unimaginable but Johnny Thomson of nearby Boyertown, Penn., proved it could be done when he toured “The Big Left Turn” in 59 minutes and 53 seconds on June 2, 1957. The time was not only a track record at Langhorne but an American and World record as well. Thomson’s average speed was 100.194 miles per hour, shattering Jimmy Bryan’s previous best of 97.56 mph. Over 25,000 race fans watched the dominant Thomson finish 31 seconds ahead of fellow Pennsylvanian Eddie Sachs of Allentown.

Sachs would shed the bridesmaid role the next year, June 15, 1958, as he wheeled Peter Schmidt’s Offenhauser to victory in 1 hour, 5 minutes and 26 seconds. However, the 26,000 race fans in attendance would have to wait nearly two hours for the completion of the race. Johnny Boyd of Fresno, Calif., was rounding the first turn when his car spun and caught fire. Boyd was able to escape with burns on his legs, but firefighters were unable to extinguish the blaze and after two hours, what was left of the Bowes-Seal Fast Special was towed to the pit area. When action resumed, Sachs, who started sixth, took the lead away from Jud Larson of Kansas City on lap 62 and proceed to lap the entire field en route to the win.

One hundred miles in less than an hour seemed almost unimaginable but Johnny Thomson of nearby Boyertown, Penn., proved it could be done when he toured “The Big Left Turn” in 59 minutes and 53 seconds on June 2, 1957. The time was not only a track record at Langhorne but an American and World record as well. Thomson’s average speed was 100.194 miles per hour, shattering Jimmy Bryan’s previous best of 97.56 mph. Over 25,000 race fans watched the dominant Thomson finish 31 seconds ahead of fellow Pennsylvanian Eddie Sachs of Allentown.

Sachs would shed the bridesmaid role the next year, June 15, 1958, as he wheeled Peter Schmidt’s Offenhauser to victory in 1 hour, 5 minutes and 26 seconds. However, the 26,000 race fans in attendance would have to wait nearly two hours for the completion of the race. Johnny Boyd of Fresno, Calif., was rounding the first turn when his car spun and caught fire. Boyd was able to escape with burns on his legs, but firefighters were unable to extinguish the blaze and after two hours, what was left of the Bowes-Seal Fast Special was towed to the pit area. When action resumed, Sachs, who started sixth, took the lead away from Jud Larson of Kansas City on lap 62 and proceed to lap the entire field en route to the win.

Van Johnson, the Bally, Penn., mechanic, not the Hollywood movie star, would have 25,000 fans roaring their approval as he upset the field on June 14, 1959. Johnson, who started 11th, drove a steady without taking any pit stops and won the 100-miler in 1 hour and 16 minutes. The car, completed the day before, had no number on it during qualifying and the crew slapped on the number “56” with duct tape moments before the green flag unfurled. Johnson took over the lead when race leader Elmer George pitted on lap 72.

Jim Hurtubise of Lenox, Calif., would win the 100-miler on June 19, 1960, but tragedy would overshadow everything else that day as Jimmy Bryan would die tragically on the first lap of the race. The 33-year-old, who had come out of semi-retirement, was attempting to pass Don Branson of Champaign, Ill., when his car suddenly skidded sideways and rolled several times. He was dead on arrival to a local hospital with head and chest injuries.

Eddie Sachs, who viewed the tragedy from behind, blamed the accident on Bryan’s “overconfidence in himself and his eagerness to return to the profession that he was so wonderful in.”

“Jimmy Bryan tried to drive a newly designed car that he wasn’t familiar with,” Sachs said. “He tried to drive it into a front running position immediately.”

“I was about 40 feet behind and could see everything. They had just dropped the green flag and the cars went into the turn. Bryan took the outside and the dust and dirt got heavy. He didn’t like what was happening, so he tried to change his strategy and cut to the inside and that was his fatal mistake.”

“He tried to drive from the outside to the inside too quickly and that put the car out of control. He made such a sharp turn that the car flipped to the inside of the track.”

After the race was restarted, Hurtubise would set a national record of 100.786 miles per hour and a time 59 minutes and 31 seconds, breaking Johnny Thomson’s mark set 1957.

“He tried to drive from the outside to the inside too quickly and that put the car out of control. He made such a sharp turn that the car flipped to the inside of the track.”

After the race was restarted, Hurtubise would set a national record of 100.786 miles per hour and a time 59 minutes and 31 seconds, breaking Johnny Thomson’s mark set 1957.

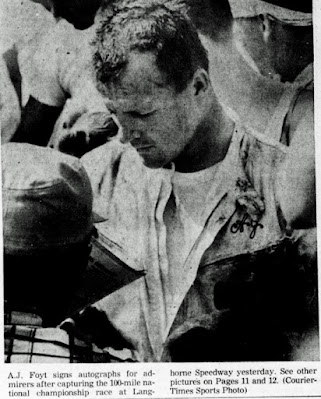

A.J. Foyt, the 1961 Indianapolis 500 winner, scored the victory at Langhorne as well on June 18, 1961. “Lady Luck” who rides alongside all winners of auto races, apparently didn’t have as much to do with the race as it first appeared.

According to the scorers and the public address announcer, defending winner Jim Hurtubise was in the lead from the 33rd to the 94th lap, when his engine conked out and he was forced out of the race.

Foyt, who was running second at the time, took the lead and won the race six miles later, and the fans in the grandstand were talking only about how “Lady Luck" was working overtime in Foyt’s behalf.

When the race was over, Foyt and his pit crew complained to the officials and scorers. They argued that Foyt did not take the lead on the 94th lap but that A.J. was actually leading the pack ever since the 44th mile.

Foyt said that on the 44th lap Hurtubise took a spin into a ditch, and he passed him. Hurtubise readily admitted this after the race. It only took him 10 or 15 seconds to get back into the race but by this time, Foyt was way ahead.

However, Foyt’s scorer missed scoring him for the lap. After Foyt’s complaint, a recheck of the records showed that he was right. Either way, Foyt won, but he didn’t want to be tagged the “Lady Luck” driver.

An announcement was made over the public address system about the mistake, but by this time most of the 28,000 fans had already left.

It was a record purse as A.J. won 25% of the $22,300 ($5,575). Not bad for an hour’s drive.

A.J. Foyt would successfully defend his Langhorne title on July 2, 1962, in a race marred by the death of Hugh Randall. The race, originally slated for June 24, was postponed 15 minutes before the start because of heavy showers and moved forward one week. Starting in the third position behind pole sitter Jim Hurtubise and fellow front-row starter Don Branson, Foyt would power past both of them on the first lap and never look back, finishing 12 seconds ahead of Parnelli Jones of Torrance, Calif.

Randall, a 23-year-old Louisville, Ky., driver fairly new to the USAC ranks, was killed when his car hit a rut and shot about 20 feet into the air, vaulting end-over-end five or six times. It landed on its foil and turned over, pinning Randall. Randall was still alive when rescue workers freed him from the car, but Randall was dead on arrival at the local hospital.

Coincidently, the same car that killed Randall, the Vargo Special, had taken the lives of two other drivers in 1960, Dick Linder at Trenton (N.J.) Speedway and 1959 Langhorne winner Van Johnson at Williams Grove, Penn.

A.J. Foyt would continue his success at Langhorne, pulling off a “hat trick” so to speak in 1963. Foyt would not only win his third consecutive 100-mile national championship race on June 23, but also win a USAC sprint car race on April 7 and a USAC stock car race on May 5. Foyt would fight off magneto problems on his car the last third of the race and still win ahead of fellow Texan Jim McElreath by 20 seconds.

Foyt would continue his dominance and on June 21, 1964, fighting heat and power steering issues, would lead all 100 circuits to win his fourth USAC national championship 100-miler at “The Horne”.

“I can’t remember ever being so tired,” Foyt remarked afterwards.

The steering on his new Sheraton-Thompson Special went out about midway through the contest and he wrestled with the car for the remaining 50 miles. He was hard-pressed by Don Branson the entire time but still won by a straightaway.

Foyt's winning time was 58 minutes and 30 seconds, an average speed of 102.522 miles an hour. The temperatures on the surface of the track were reported to be 125 degrees.

Before the 1965 race was to take place, Langhorne promoters Irv Fried and Al Gerber had the track's layout reconfigured to a "D" shape by building a straightaway across the back stretch and paving over the uneven dirt surface with asphalt.

When the annual 100-miler took place on June 20, 1965, a throng of 39,120 spectators witnessed the “new” Langhorne Speedway and watched as 37-year-old Jim McElreath break Foyt’s four-race winning streak.

The race itself boiled down to a two-man event. The only leaders of the race were McElreath for 68 laps and the “Italian Import”, 25-year-old Mario Andretti of Nazareth, Penn., who led 32 circuits. The average speed was 89.108 miles per hour, which was slowed by numerous accidents.

Andretti broke Don Branson’s old qualifying record, with a clocking of 30.46 seconds for an average speed of 118.187 miles per hour. Branson’s record was 31.580 seconds, 113.996 miles per hour.

Foyt qualified in fifth place but retired from the race on the 29th lap after his car developed overheating problems. It was then announced afterwards that Foyt and his chief mechanic, George Bignotti, had split up. It had been rumored for some time and it finally happened following an argument in the pits that Sunday afternoon.

When the afternoon ended on June 12, 1966, Langhorne Speedway was once again the home of the world record for a mile track. Mario Andretti batted 1.000 that Sunday as 26,200 fans watched him establish a world record in the time trials and then go out and win the 100-mile National Championship Car race, leading all the way.

Andretti, piloting the Dean Van Lines Special, lowered the world qualifying mark to 29.36 seconds, touring the D-shaped oval at 122.615 miles per hour. He then led all 100 laps, winning in 1 hour and 47 seconds, in a race slowed by 30 laps run under caution. In fact, Mario took the checkers under the caution flag – the first time in the 40-year history of championship racing. Andretti’s victory earned him about $8,000 of the total purse of $27,300.

Al Unser of Albuquerque, N.M., and Lloyd Ruby of Wichita Falls, Tex., would put on a two-man show on June 18, 1967, at before 26,235 fans at “The Horne”. They each led for half of the 100-mile national championship car race.

Unfortunately for Unser, however, he led for the first half. Ruby, driving a brand-new car, took over the lead on the 53rd lap and led the rest of the way. He crossed the finish line in 52 minutes and 55.16 seconds, setting a new track record for the distance. The average speed was 113.380 miles per hour. That shattered the old marks set by Don Branson in 1962 of 57 minutes and 15 seconds (104.799 mph) when the racing surface was still dirt.

Unser himself would break Mario Andretti’s world qualifying mark for one-mile tracks when he sped around Langhorne in 29 seconds flat, averaging 124.137 miles per hour.

By 1967, offers from developers became too tempting to refuse for Fried and Gerber and it was announced that Langhorne Speedway had been sold. But the speedway did manage to hold on through five more seasons.

The USAC championship division would continue to compete at Langhorne for the next few years, but the event was changed from the traditional 100-mile race to 150 miles. Gordon Johncock of Hastings, Mich., would win the 150-miler on June 23, 1968, while Bobby Unser of Albuquerque, N.M., would win the last two USAC races, June 22, 1969, and June 14, 1970.

No comments:

Post a Comment